Hand-Powered Far Field Interaction - How We Did It¶

by Pip Turner, Research & Development Engineer

Our hands are powerful tools that allow us to interact with anything within reach. In XR, hand tracking gives us the power to use our hands to move beyond our physical reach and directly interact with out of reach objects.

Far field interactions have become an essential tool. They are used in almost every XR application so it’s important to get them right. If we introduce too much friction between you and the object you want to interact with, we risk ruining a fundamental part of the experience.

The backbone of far field interactions is the (often invisible) line between the hand and the object - the hand ray. The direction is generated from how we position our body.

Our most recent release of the Ultraleap Unity Plugin has a hand ray in early preview form. But how did we work out where you’re pointing? And how did we make it nice and stable?

Heading in the right direction¶

We needed to find a way to create a direction that was both natural and stable enough for us to rely on. This is best described by using a ray, defined by MathOpenRef as:

A portion of a line which starts at a point and goes off in a particular direction to infinity.

For our far field interactions, the ray is the line we use to aim. It comes out from our hand and into the world.

To calculate far field rays, we tend to use two positions - a primary position and a secondary position. The obvious place to initially cast from would be the wrist - it follows our hand’s general direction and points in a place that would seem sensible.

The problem is that hands have a small amount of natural jitter that gets amplified over large distances when ray casting. Instead of using the wrist, a now widely used method for working out a far field ray’s direction is to cast a ray out from a shoulder position, which gives the ray some nice stability.

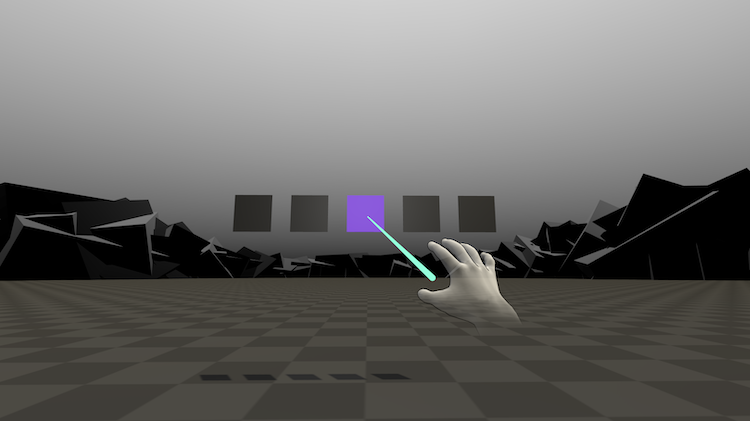

Wrist Ray

Shoulder Ray

You can see in these clips that a ray defined by using the wrist as a secondary position is jittery. It’s very well connected to the hand and the ray follows as you move your hand in any direction. But any jitter from the hands gets magnified over distance. The wrist position feels overly sensitive and difficult to control - a similar feeling to suddenly increasing your mouse’s DPI.

Using the shoulder position gives us a much more stable ray, but it feels disconnected from our hand movements. When we rotate our hand, the ray doesn’t follow the hand’s rotation. Losing this degree of freedom reduces our hands down to a being a 2D pointer. This limits both expression, and the potential of far field interaction. As well as this, the shoulder position being derived from the head can bring in a lot of unwanted movement not caused by the hands, but the head. This can mean that even if our hand is completely still, the position we are aiming at can change.

We wanted something that combined the benefits of using the wrist and the shoulder. Something more connected to the hands than the shoulder position, but more stable than the wrist position.

A natural ray¶

As mentioned, when casting a ray we use primary and secondary positions.

Let’s call the primary position, the Aim Position. This is where the ray is cast through and out in the world. It heavily influences the direction of the ray and is often directly connected to your interaction. In our testing, we were using pinch as our primary interaction, so our Aim Position was the pinch point. If would have felt very odd if we were using pinch and decided to use the little finger tip as our Aim Position!

We’ll call the Secondary Position, the Ray Origin. This is where the ray is cast from, and it’s the secret sauce in getting a good ray. As we saw earlier, where you place this defines the entire behaviour of your ray - place it on the wrist and you get an expressive ray, sensitive to hand rotation. Place it on the shoulder and you get a stable ray, but one which is very insensitive to hand rotation.

It makes sense then, that we found that setting the Ray Origin to a midpoint between the wrist and shoulder gave us a ray which inherited some of the stability of the shoulder, and some of the expressive nature of the wrist, following our hand’s rotation without feeling overly sensitive and hard to control. Using this midpoint produces a ray that feels connected to our intent.

A stable ray¶

We now have a great foundation for our ray - casting from a midpoint between a shoulder position, and a wrist offset and out through the pinch position. This gives us a really flexible, expressive ray. However, our work is not done yet - whilst it is natural, our ray still needs some work to get to a good level of stability.

Where are our shoulders?¶

In XR, we only really know the positions of your hands, and your head. Therefore, we need some way of working out where your shoulders are. Our first solution to this was to simply connect our shoulders directly to the head. Whilst this initially worked well, it produces some fun side effects!

On our real bodies, our shoulders aren’t connected directly to our head, they’re connected to our necks. To get better shoulders, we created an estimation of the neck position which allows us to represent our shoulders more closely to how humans work, and increase the predictability of our ray.

Jitterbug¶

When we were testing, we were reminded of the great lesson that things which are far away, are also very small. Aiming at small things takes a lot of concentration and really highlighted unwanted movement being introduced to our ray. A lot of this came down to jitter being introduced into our ray, causing it to move when we didn’t want it to.

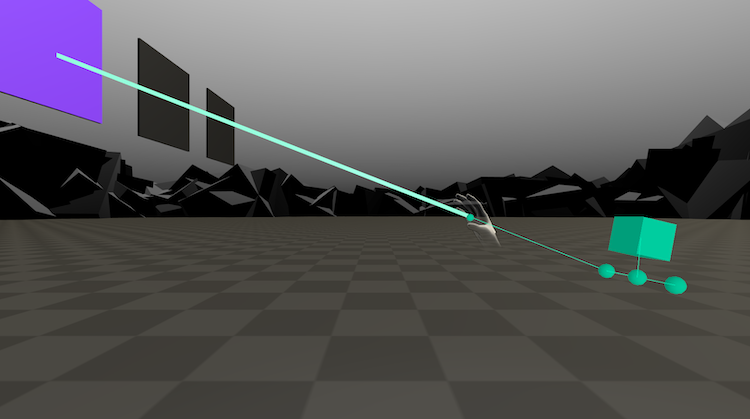

Aiming at small targets can be useful in settings such as trying to target handles connected to objects, or hitting small buttons on an interface way out in the distance.

We built the scene above for testing. It’s essentially a Whac-A-Mole with extremely far away targets, and smaller but closer targets. In real world applications it’s unlikely that we’ll face as complex situations as these, but testing with extremes allows us to target the best performance possible.

This helped us identify two areas of potential improvement:

Reducing hand and head jitter through filtering

Reducing unintended ray movement through a more stable pinch position

Reducing hand and head jitter¶

Jitter can be introduced through both natural movements (a wobbly hand) and tracking errors (e.g. jitter from hands being at the edge of the interaction zone). We can remove a lot of unwanted jitter simply through running our Ray Origin and Aim Position through a filter.

We applied the 1€ Filter to our ray. It’s built with the intention of minimising jitter and lag when tracking human motion. There’s a great online demo of it here.

Thanks to the wonders of open-source software, a unity implementation of it already exists. After taking time to tune the filter (very important!), we get the following result:

The above video shows the effects of filtering our ray. When off, you can see how noisy the ray’s values are. Even with our hand relatively still, the ray continues to move, and when our hand is moving the ray’s trail is far from smooth. When on, there is a lot more stability when our hand is relatively still, and the ray’s movement became a lot smoother.

Reducing jitter means weaving some magic 🪄¶

The pinching action is another source of unintended movement. This was really apparent when doing precise targeting - you line up your target, start to pinch, and by the time your fingers meet the ray has drifted off the button, so you miss.

Our tools currently provide you with a pinch position designed for interacting at the point the index and thumb meet. It’s great for displaying where the pinch position is, but not so great for extreme stability.

Instead of using the predicted pinch position, we use a static offset from the index knuckle close to where the pinch point will be, but still visually draw the ray from the predicted position. This gives the aim position the illusion of stability, even though your hand isn’t actually that stable.

Conclusion¶

Far field rays are one of the most extensively used tools in XR. By combining them with hand tracking, we’ve enabled direct interaction with objects much further away than we’re able to reach.

Traditionally far field rays have been cast from the shoulder position, through an aim position. This has resulted in an experience that can feel disconnected from the hand - not fully utilising the hands full expressive nature.

Using a ray origin located between the wrist and the shoulder reconnects the ray to the hand, without causing the ray to become too sensitive and unusable. Then, by better estimating our shoulder position, filtering our ray, and using a more stable pinch position we can increase our ray’s reliability to similar levels to the shoulder position. We now have a powerful and expressive tool for our XR needs.

Try it out, and create your own, using our Unity Preview Package. As this is an early preview, we would love all your feedback (both good and bad!). Please reach out to us on Discord or via our GitHub Discussions.